‘Collectors’ journeys into the homes of fledgling and seasoned art buyers from across the globe. The ongoing series offers an intimate spotlight on a range of personal collections from hobbyist ephemera to blue-chip artworks — all the while dissecting an individual’s specific taste, at-home curation and purchase trajectory.

For Hannah Traore, the latest gallerist to open shop in New York’s Lower East Side, art is always entwined with education. At just 24 years of age, Traore has quickly ascended in the world of art for nurturing a genuinely inclusive suite of exhibitions that gives voice to marginalized communities.

Born and raised in Toronto to a White mother and a Malian father, Traore is one of the many who is tired of hearing the words ‘diversity equity and inclusion,’ as if by slapping these terms on a campaign or press release, equality will suddenly be achieved. “You can’t just sign a Black artist without doing your deep research and it shouldn’t be up to the artist to educate you either,” Traore tells Hypeart.

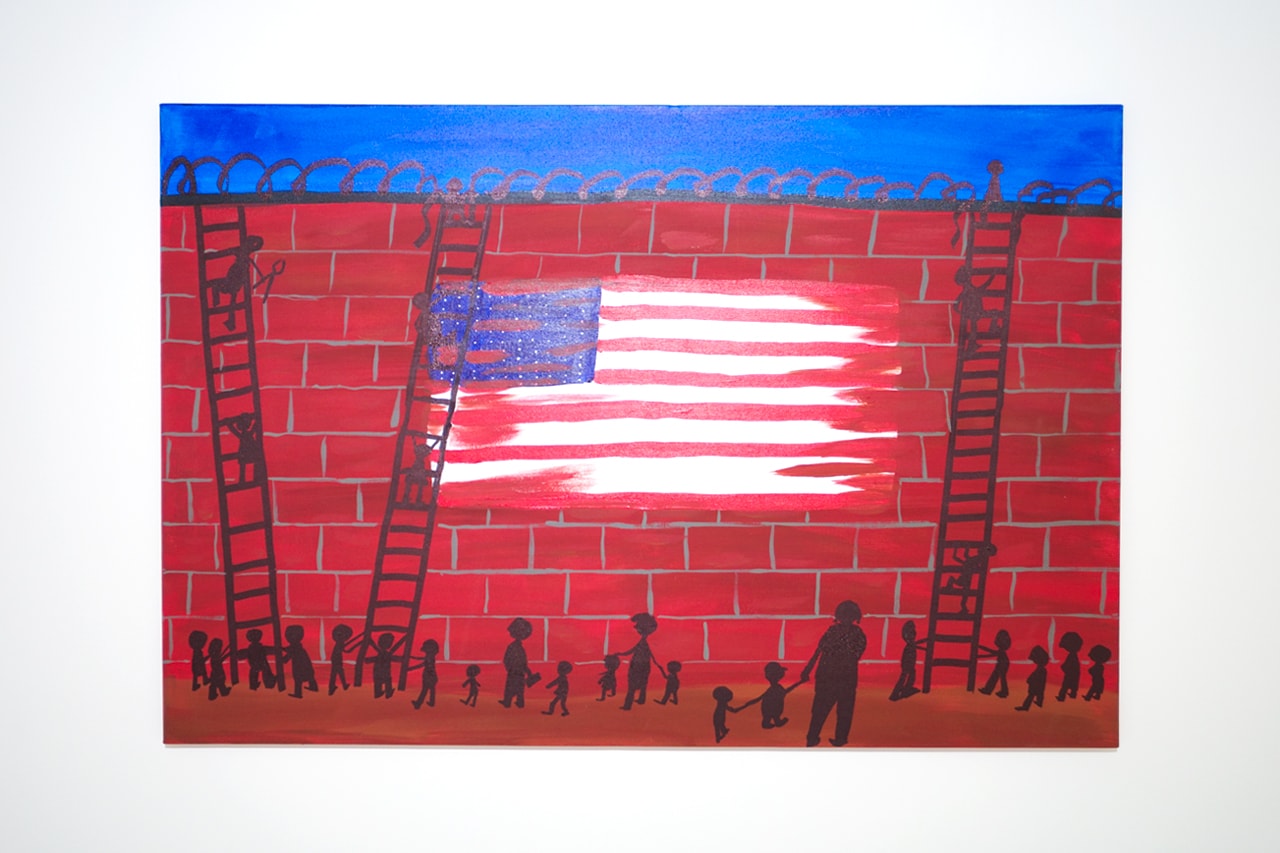

Entering her second year, Traore’s namesake gallery has already worked with scores of established and emerging artists, including Camila Falquez, James Perkins and Moya Garrison-Msingwana. One of her latest shows? A presentation of work by the nearby grade school.

“It’s so important for kids to see themselves in us – representation is crucial. It can change lives,” Traore says. The gallerist collects a piece from each show she exhibits, along with a wealth of beautiful work, such as those from her native Mali and archival pieces from the history of fashion.

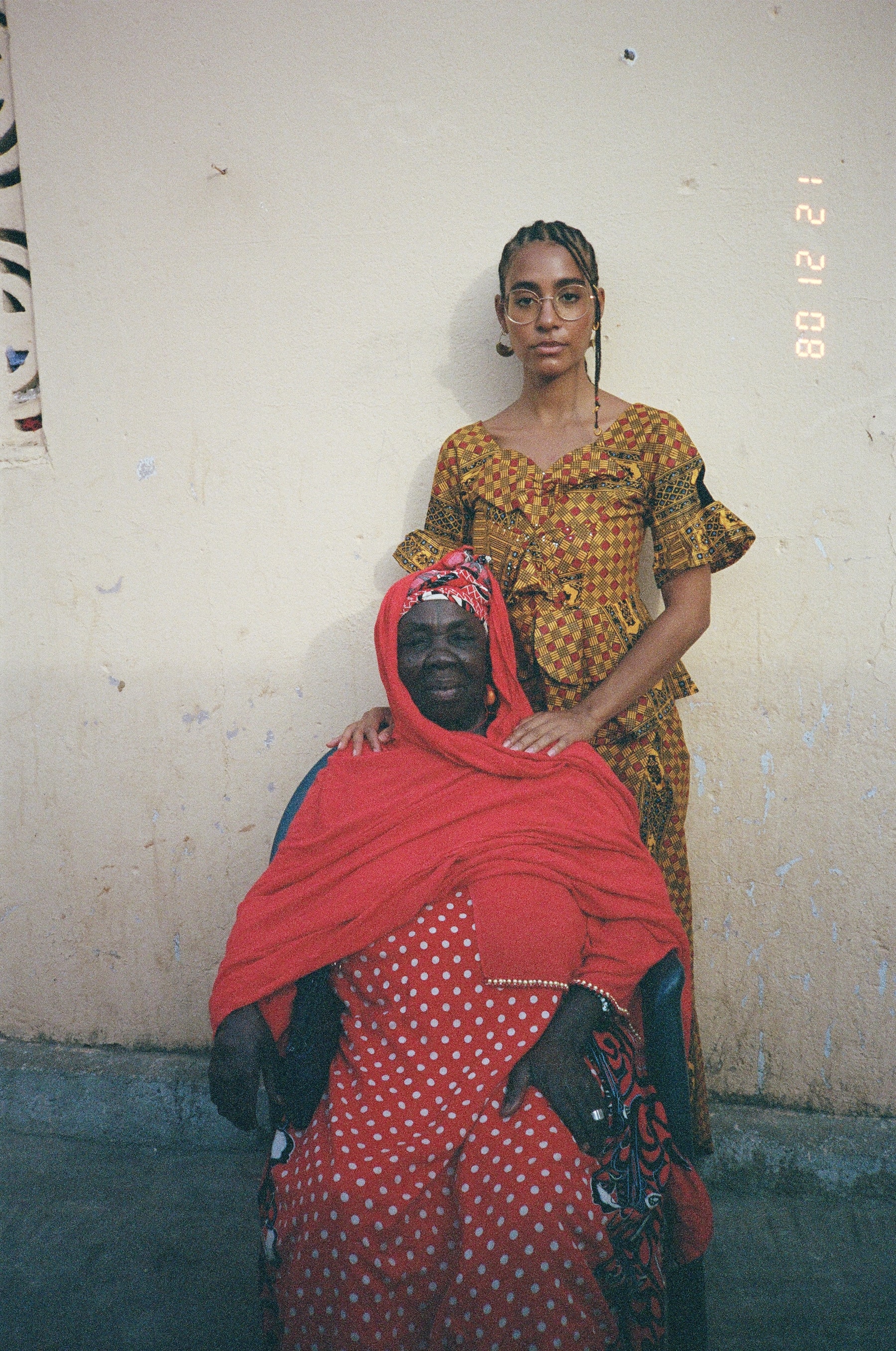

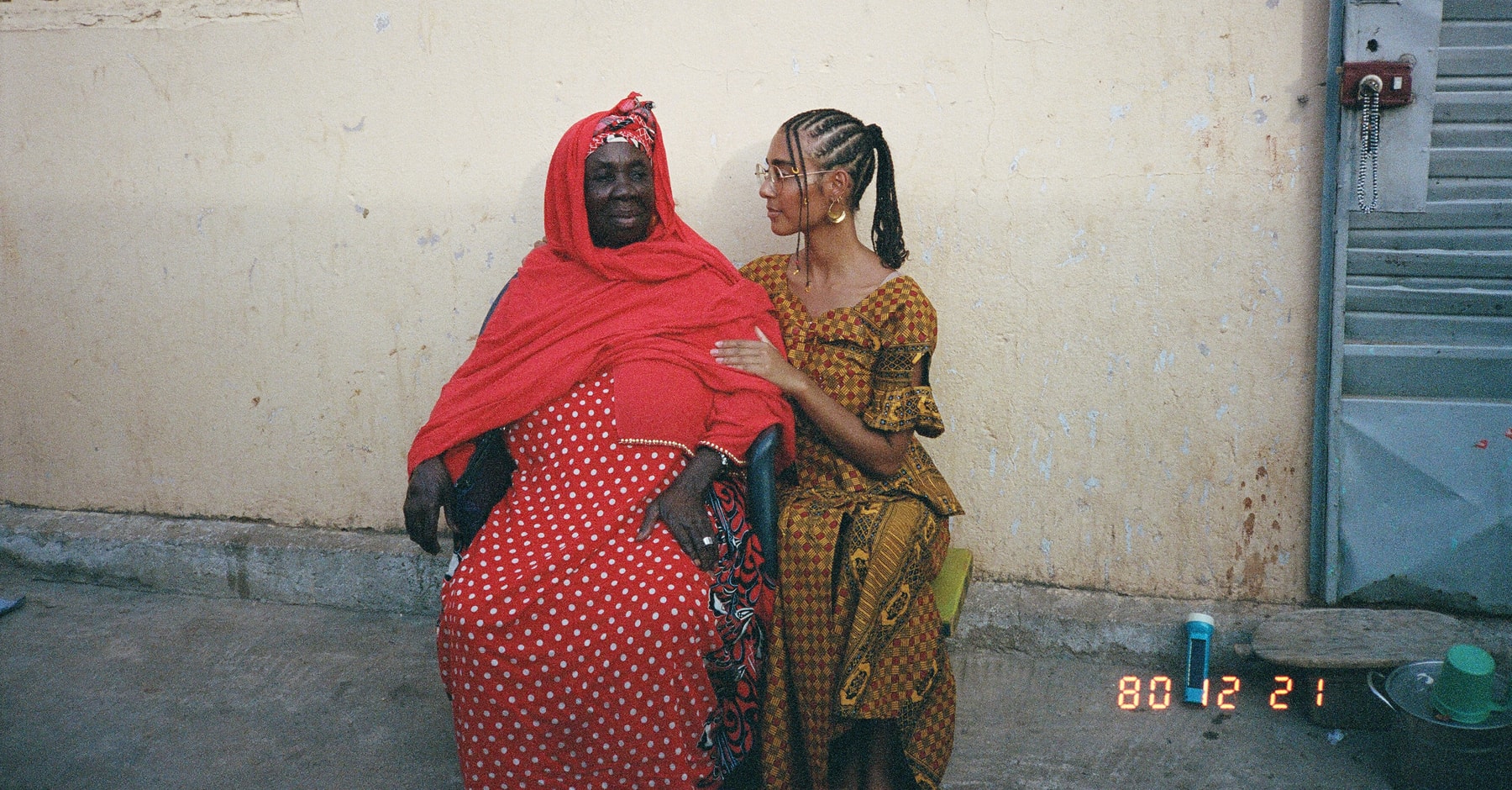

Coming off a recent trip to Mali and her gallery’s inclusion at Frieze Los Angeles, Hypeart caught up with Traore to learn how she got started at such a young age, why her gallery stands out amidst the storied NYC art scene and what we can expect in the months ahead.

“I grew up in a world of opposites.”

How did your journey in art begin?

I wouldn’t say that it really began anywhere, because I was really born into the arts. My mother grew up as an artist, though I don’t know if she would consider herself one today. When she was around my age, she would go to West Africa and bring back art and sell it in Toronto — which is how she met my father, because she was in the West African community within Toronto.

Because of my mom’s love for the arts, everything in our lives was infused with creativity. Our kitchen was filled with me and my three siblings’ artwork — from head to toe. On weekends, we would always do arts and crafts like tie dye shirts for my dad and his brothers on Father’s Day, origami boxes for all our classmates on Valentine’s Day — everything was art. I was taking darkroom photography in grades three or four, which is crazy. Now, my mom encourages all our cousins to go to that same class.

When people ask, ‘do you remember the first time you fell in love with art?’ I say no, because I just grew up in it and didn’t know any different. I feel so lucky that I grew up in the way that I did, and because of it, I never felt like I was disappointing my parents by being an art history major. There is a lot of privilege that comes with that and I can’t lie, on my father’s side, many of my uncles and aunts are confused why I’m not a lawyer or a doctor, which is a very common opinion amongst West African immigrants, or immigrants in general, maybe.

Even after opening my gallery, my uncle was like, ‘I don’t understand, you’re so smart, why don’t you be a doctor?’ Because I have no interest in becoming a doctor haha. I thought I was going to be a primary school teacher my entire life until my sophomore year of college. I’m obsessed with kids, maybe even more than I’m obsessed with art. I respect teachers more than any other job. After taking psych classes, and thinking about majoring in Classics, social work, or education, I took an art history class and everything changed.

I love art and I love history and don’t know why I never thought of art history as an option. It’s the path that made the most sense and made me the most happy.

“You can’t do it alone.”

Having a Canadian, West African, Muslim and Jewish background, can you talk about how each piece of your identity shapes your worldview?

I’m so proud to be the daughter of an immigrant who can’t read or write in any language and the daughter of a college educated woman. So proud of both and it shapes everything that I do. You can’t understand what it’s like to walk in someone else’s shoes, like I’m not going to understand how it is to have to come out to your parents as a queer person. I can try to relate and try to understand but I’m not going to truly know. Because I grew up in a world of opposites — Jewish and Muslim, White and Black, African, Canadian and so on, I know what it feels like to be a lot of different things, which gives me a unique perspective; but it also gives me an opportunity to try to understand other people’s experiences at a deeper level.

For those who are unfamiliar, can you describe Malian art?

Mali is a really interesting country. It is one of the poorest countries in the world, but is so incredibly rich in music, art, history, and culture. The first ever university was in Mali, as was the richest person to ever exist— Mansa Masa, but people often mistake me for saying Malawi or Bali because they haven’t heard of it and I’m always like, ‘no, no, no… it’s one of the biggest countries in Africa…come on.

Usually the art that people think of as “African” is actually West African. You can find wooden sculptures and masks all over the continent, but those types of artifacts and artisan works originate from West Africa, which shows the importance the region has had on the rest of the continent and world. Also there’s a reason I keep saying “West Africa” — borders everywhere, but specifically all over Africa are completely arbitrary and made by colonizers. For example, my dad’s village is in Mali, but the soccer field is in Senegal — literally a two minute walk.

Also visually, the fabrics are something that’s really important to note. My cousins will wear the most beautiful fabrics just to go to school or wash the dishes — it’s a part of their culture. Everything is very aesthetic.

“True representation comes from true understanding.”

Can you take about your days at Skidmore?

The Tang Museum on Skidmore’s campus, and specially Ian Berry and Rachel Seligman, are one of the main reasons why I’m here today.

Sometimes students will curate an exhibition in the hallway, but in my senior year, I went to the museum director, Ian Berry, and proposed curating an exhibition for my senior thesis in one of the actual galleries. I feel so lucky to have gained his trust, because I had never done anything like it before. It was also totally serindipitus that there was an opening in one of the galleries to house my show, and that they had just relied a grant to collect work. It was a complete dream that I was able to curate an exhibition which included artists like Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, Derrick Adams, Zanele Muholi, and Hassan Hajjaj, who ended up being my first installation at my gallery.

How was the MoMA experience?

As an intern at MoMA, you really do learn. They’re really focused on education. Once a month, we would go to a different exhibition and they expose you to the New York art world. I worked in the Painting and Sculpture department and was doing real work, like writing for the exhibition, which I would see my text on the wall. The problem with MoMA is that it’s such a well-oiled machine, that you stay in your lane. There were some points where I had nothing to do and had to ask and beg for work, so I would go three hour stretches with nothing to do. But also, I was in charge of the mail, which was my favorite part of the day, because I’d open the mail and it was so interesting.

I was also the Black Arts Council intern, which funds one internship a year. I was lucky that that year it was mine, so I went to all of their events and got to know the members. Immediately when I left the internship, I joined myself, because it was such an important part of my life in New York. It feels like family. It was incredible, because that is a community of individuals who are interested in Black art interested in helping MoMA filter our black art collection. So we’ve been doing studio visits, tours and exhibitions with the artists or the curator.

“People always say that sports save kids, but I think that art saves a different kind of child.”

Can you walk us through how your gallery started?

I think I knew I would open a gallery one day after that experience at the Tang or at least, that’s where I first got the idea. To be honest, I always assumed I would do it a lot later in life. I’m Canadian and a visa can be precarious at times. When I switched jobs from MoMA to Fotografiska, I went home to Toronto for a weekend to get my new visa. I didn’t even bring a carry-on, just a purse, and then wasn’t let back into the country for six weeks. I was devastated — I had an apartment, a new job, friends and my whole life in NYC!

My family said, ‘well, you wanted to start a gallery…why not do it now? If this job and visa doesn’t work out, open the gallery.’ So I had that in my head and then six months later, after fixing the visa and starting the job, I was a little disappointed. I told myself, “I’ll be here for two years and then start my gallery.’ Three months go by and the pandemic hit, so I was twiddling my thumbs for a bit, and realized that it was the perfect time to start this huge project. I had enough time to really think about my vision, do research and just go for it. Also, Fotografiska was a horrible experience — most abusive work environment I’ve ever been in. Everyone I know there also had a horrible time. It was very racist and just a mess. My gallery manager also came from there and we really bonded over that shared experience.

You’re not ready to do something like that until you just do it. I am so confident in my curatorial eye and my relationships with my artists, collectors, and community, but I never worked in a gallery, nor have I ever taken a business course. I had to learn those things as I went, which is always the best school. I also think it’s so important to not pretend like you’re Superwoman. I needed help with certain things and I asked for it and still ask for it all the time. You can’t do it alone.

“Representation is crucial. It can change lives.”

Can you talk about how you set yourself apart from the historic New York art scene?

I think my gallery has some differences to other New York galleries, but I didn’t necessarily do that on purpose. I was just starting my own space, so I did whatever I wanted and that’s why it’s different. The types of artists I work with have not only been historically ignored, but also historically exploited, which I think people don’t talk about as often. A lot of artists of color and queer artists feel like they are working with a gallery because the gallery feels like it’s checking a quota. It’s very important for me that my artists feel fully seen for their work, talent and know that they are not in my gallery because they are gay or Black. They are in my gallery because their work is bomb and deserves to be seen and they just happen to be from one of those groups. I also just don’t pay attention to the rules of what constitutes art that’s viable to be seen in an arty space. For example, I have the work of about 70 students ages three to twelve in the gallery right now. Why? Because I think it’s important and I wanted to.

Diversity, equity and inclusion have unfortunately become buzz words today for marketers. What does true representation mean to you?

The amount of times I’ve heard White gallerists say, ‘Black art is a trend.’ Don’t speak about us like we’re a f*cking trend. We’ve always been here and will always be here and the fact that you see it that way is exactly what I’m talking about. True representation comes from true understanding. Education is so important – you can’t just sign a Black artist without doing your deep research and it shouldn’t be up to the artist to educate you either. It’s so easily performative and there’s layers to it.

Performativism is so so dangerous. I talk about this all the time. Especially after George Floyd was murdered, every gallery in New York City was showing Black figures. Why? Because they wanted to prove that they were showing Black artists. If the artist is abstract, you can’t tell they are Black. My artist James Perkins is a good example. He’s said to me that he felt people didn’t pay attention to him “because they can’t tell [he’s] Black by looking at [his] work.’

What ended up happening is a lot of the galleries were scrambling to sign Black artists and didn’t actually do the research and find the artists of the highest quality — which by the way, there’s millions of. Instead, they chose whatever figurative artists they could find. Some of them are amazing and others are just simply not good. It’s important to say that I’m NOT saying that Black artists aren’t good enough. There are way more than enough exceptional talented Black artists to choose from. Galleries were just being lazy about it. As much as I believe that Black people should be allowed to be mediocre, because we all know that white people are allowed, we cannot act like the world is in a place to be able to see that and understand that it doesn’t speak for our entire community. We have to be so careful, even in 2023. But these galleries don’t think about these things and frankly, probably don’t care. It’s so unfair.

“I collect work that I want to live with.”

Education seems to be such a focal point of your curation, such as the current exhibition in the center room of your gallery. Can you talk about that more?

I love kids. They’re our future. People always say that sports save kids, but I think that art saves a different kind of child. It’s really important to me to keep art alive in schools. There are so many children out there that would be artists or enjoy art as a hobby if they knew it even existed as an option for them. If you’re not exposed to something, how are you going to know?

Community is also really important to me. I don’t just want to exist in the Lower East Side without really connecting with the community around me. That’s why I choose to collaborate with three schools here within the Lower East Side. I want the kids to feel so proud and so special. Later this week, we’re going to host the artists for an opening and have mocktails and a photographer! They’ll see a Black female gallerist, a Black female gallery manager, a Black male photographer. It’s so important for kids to see themselves in us — representation is crucial. It can change lives. All the sales and are being matched by the gallery and will be split between the three schools.

It goes back to the Picasso quote of him spending his life trying to draw like a kid again. Children don’t know any better and do things or create just because they like to.

How about the show in the back?

Deborah Czeresko was the winner of Blown Away, which is a glassblowing competition on Netflix that I was obsessed with. She was one of the only ones there who wasn’t trying to make friends, not in a mean or bully way — she made friends — but had no time for other people’s bullshit, called people out, and was so conceptually interesting. She has a beautiful mind.

Funny enough, I first met her because she showed up to my gallery opening! Working with artists is my favorite part of the job and being privy to the development of their show’s with me is so interesting. We gave her a lot of time to think her ideas through and what she came up with is so brilliant. As the press release said, “mycological research affirms the message that being queer is natural. According to fungal taxonomist Dr. Patricia Kaishian, “mycology is queer at the organismal level. Fungi are nonbinary, they are neither plants nor animals but possess a mixture of qualities common to both groups upending the prevailing binary concept of nature.” Also, mushrooms are having a real moment right now in terms of being a superfood, a common recreational drug and even [appearing] in interior design.

“I really want to help change the fabric of the art world.”

Speaking on your own personal collection, what type of work do you like to bring into your home?

I collect work that I want to live with. I just bought this piece from Ochi Gallery at NADA in Miami because it just made me feel really good when I spent time with it. I put it in my apartment and living with it feels just as good — the colors, the vibe — that’s how I collect and show work.

In the gallery, I don’t necessarily have to show work that I want to live with. I think those are two different things, wanting to live with something and thinking it’s incredible. But I collect from each show because I’m sentimental and love all the artists I work with.

My dream is to collect a Malike Sidibe photograph. He’s a Malian legend and my thesis was actually based on his work and those he has inspired over the years.

There are a lot of things people collect that wouldn’t traditionally be deemed as art. Can you share some examples that fall under this framework?

Clothes for sure. As I get older, I see my shopping addiction more as collecting, because I buy less fast fashion and buy more pieces I consider art — from vintage to new designers.

A lot of fashion designers these days are making sculptures for the body. I also own clothing from my grandmother and my mother, such as Issey Miyake, COMME des GARÇONS, and Prada — all from 40 years ago. I want to be able to give those things, along with my art, to my kids. I also collect eyeglasses and have about 40 prescription pairs.

Is there a particular piece you bought recently that you were stoked on?

I bought this vintage MUGLER suit in Paris that I’m obsessed with. A few weeks later I went to the MUGLER show at the Brooklyn Museum and saw a picture of my suit in the exhibition! It’s a Helmut Newton photograph. I was so excited and feel that it really cements the suit as a collection piece.

What are your short term and longterm goals with the gallery?

Short term, you’re going to see more of the same! I want to just keep expanding my beautiful community and continue to share the work of incredible artists with the world. Something I’m excited about is my fashion collaborations. The first one is in September. This was an idea I had before opening where I bring in an artist and designer together and we put together a capsule collection. I don’t want it to be a situation where we just slap a photograph onto a pair of pants. I want it to be a conversation and true collaboration between industries and mediums.

Longterm, I really want to help change the fabric of the art world. Not necessarily to get rid of one part, but to help inspire people to do whatever the f*ck they want. The art world would be more interesting if people were doing that.

Photos courtesy of Hannah Traore and Shawn Ghassemitari for HypeArt.